The news media has reported that more and more students are priced out of college or going deep in debt to pay for it, diminishing their prospects for the rest of their lives. Higher education debts have been blamed for constricted career choices and deferred homeownership, marriage and parenting. Based on that reporting, the story I had prepared to tell was that soaring tuition at private colleges may be explained by an arms race for extraneous amenities, extra administrators and increasingly cosseted faculty. But in public higher education, which accounted for 73.1% of higher education enrollment in 2012, cutbacks in taxpayer subsidies are the greater factor.

This is the story told by the public colleges and universities themselves. According to a recent report from Demos cited here,

“Cuts to higher education funding by state governments accounted for 79% of tuition increases at public research universities between 2001 and 2011 and 78% of the growth in college costs at public bachelor’s and master’s universities.” “Some have argued that universities’ penchant for hiring more administrators and constructing more buildings are the primary culprits behind skyrocketing tuition” according to this source. “While this so-called administrative bloat is an issue worth some attention, the report argues that it hasn’t played as large a role in tuition hikes as state funding cuts or the rising cost of health care for university employees.”

The data is a bit more complicated.

This is the latest in a series of posts based on my compilation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Census of Governments. The main spreadsheets, where the data came from, and how it was compiled may be found in this post.

My prior analysis of public higher education employment, based on the employment phase of the 2012 Census of Governments, is here.

A table of data for State Government Higher Education for all states can be downloaded here:

One key point about the Census Bureau’s data: it is on a cash basis. As a result, very large expenditures that are in fact paid for over time can make spending seem very high in any one year. One example of this, which caused Pennsylvania to be excluded from one of the line charts below, involves a large capital construction expenditure in FY 1992. A little online research shows a second deck was added to Penn State’s stadium that year.

The Bureau divides higher education expenditures into two categories: auxiliary enterprises and other. Auxiliary enterprises include:

Higher education activities and facilities that provide supplementary services to students, faculty or staff, and which are self-supported (wholly or largely through charges for services) and operated on a commercial basis…Dormitories; cafeterias; bookstores; athletic facilities, contests, or events; student activities; lunch rooms; student health services; college unions; college stores, and the like.

Other involves the actual education, including all related activities for instruction, research, public service (except agricultural extension services), academic support, libraries, student services (other than self-supporting enterprises), administration, and plant maintenance.

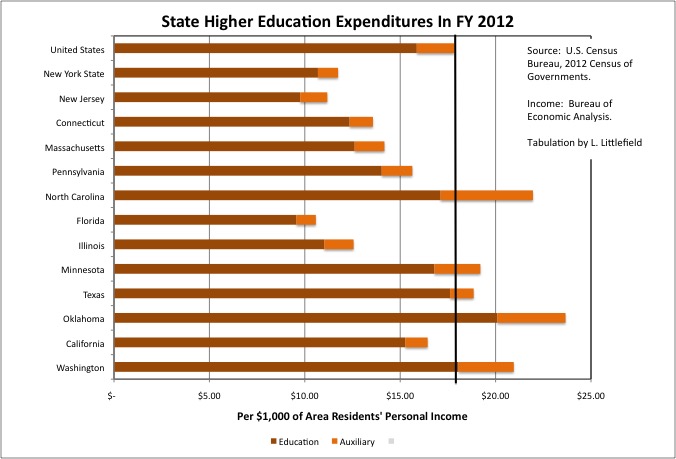

So how much did state governments spend on higher education, compared with the income of all state residents, in FY 2012?

The FY 2012 U.S. average was $17.83 spent on state government higher education per $1,000 of U.S. residents’ personal income, including $15.87 for education and $1.96 for auxiliary expenditures. New York State was much lower at $11.74 per $1,000 of personal income overall, $10.69 for education and $1.06 for auxiliary. Relatively low state expenditures on public education are common in the Northeast, where private colleges were established before the development of public higher education. Expenditures totaled just $11.18 per $1,000 of state residents’ personal income in New Jersey, $13.57 in Connecticut, and $14.17 in Massachusetts.

This compares with $25.81 in Michigan and $21.35 in Wisconsin in the Midwest, and $21.96 in North Carolina and $23.66 in Oklahoma, in the South and Southwest, and $20.95 in Washington in the West. But state higher education expenditures also below average per $1,000 of personal income in California ($16.44) and Illinois ($12.56).

New York’s low public higher education spending, therefore, is in part explained by low public enrollment as a product of history. Whereas public colleges and universities account for 73.1% of total U.S. enrollment, the figure for New York State is 54.7%. Although 80.2% of those attending colleges and universities in New Jersey attend public institutions, a large share of New Jersey’s students attend schools outside that state, including in Upstate New York. The State University of New York “was officially established in February 1948 when New York became the 48th state, of the then 48 states, to create a state university system.”

https://www.suny.edu/about/history/

The institution as we now know it was built during the administration of Governor Rockefeller in the 1960s. The City University of New York, whose four-year colleges are also counted as state government institutions, is older, but it too was formally established as CUNY only in 1961, and expanded rapidly in that decade.

http://www.cuny.edu/about/history.html

Private higher education is a major industry in New York State, particularly in Upstate New York, as demonstrated by this chart of private college and university enrollment per 100,000 residents.

A relatively low share on enrollment, therefore, explains part of New York’s relatively low state higher education expenditures. So does that fact that community colleges are counted as local government operations in New York.

Nonetheless, one does get the sense that New York State’s spending on public higher education is relatively constricted. This is a state where the legislature is dominated if not controlled by producers of public services, the public employee unions and private contractor organizations, a state with the highest state and local tax burden – exclusive of mineral extraction taxes. The news is full of demands for New Yorkers to pay more, or expect less in exchange. But somehow SUNY and CUMY are left out of this, and are generally expected to do more with less.

The proof? The $11.74 per $1,000 of personal income spent by New York State is low even compared with other states with similarly low shares of total higher education enrollment in public institutions. In Iowa the share of students in public institutions is 54.7%, the same as New York, but spending on public higher education, at $21.35, is much higher. Pennsylvania also has just 54.7% of enrollment in public institutions, and higher spending at $15.64. Arizona spends $15.70 per $1,000 of its residents’ personal income on state higher education, even though just 47.0% of that state’s students are in public institutions. And Massachusetts has just 43.1% of its total enrollment in public institutions, but spent $14.17. (In the case of Massachusetts, however, the large number of students from other states in public colleges and universities pushes down the percent enrolled in public colleges and universities).

Focusing on education alone and excluding auxiliary expenditures, state government spending on higher education has increased over in most states as a share of state residents’ income over the past 20 years. U.S. state government spending on higher education increased from $13.13 per $1,000 of personal income in the U.S. in FY 1992 to $14.35 in FY 2002 to $15.88 in FY 2012. That is a 20.9% increase in spending, relative to the income of the taxpayers, students and parents that have to pay for it, in 20 years. In New York State the increase was from $8.53 to $8.91 to $10.22, with an increase of 19.8% relative to income over 20 years.

State higher education spending increased 15.8% relative to income in New Jersey, 53.2% in Massachusetts, 48.2% in Connecticut, 35.0% in North Carolina, 30.0% in California, and 31.7% in Texas. A higher share of someone’s income is going to be paid in some form to cover it. Pennsylvania was an outlier with a 1.8% decrease relative to income over 20 years. So it would certainly seem that public colleges and universities are spending more, as a percentage of the income of taxpayers, parents and students who have to come up with the money.

This increase is explained by rising enrollment, but only in part.

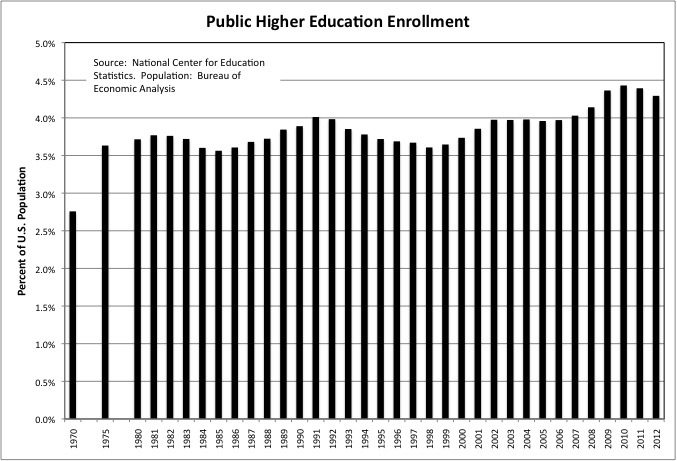

According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics and the Bureau of Economic Analysis (population), public higher education employment equaled 4.0% of the total U.S. population in both FY 1992 and FY 2002, but 4.3% of the population in FY 2012. That is a 7.8% in enrollment relative to population over 20 years. But all of that increase took place during the Great Recession – public higher education enrollment was just 4.0% of the population in 2007. So it can’t explain increased spending before that point.

For state and local government combined, and thus including all community colleges, higher education expenditures fell from 1.56% of U.S. residents’ personal income in 1972, when the first half of the Baby Boom generation was in school, to less than 1.35% of income from 1979 to 1985, the late boomers and Gen X was in college. But enrollment does not explain this. Public higher education enrollment totaled 2.8% of the U.S. population in 1970, according to data from the NCES and BEA, but it increased to 3.7% of population in 1980 and stayed at about that level through the 1980s. That was clearly an era of falling spending on higher education relative to enrollment, although that might be explained by falling capital expenditures. The buildings constructed for the first half of the Baby Boom were still there for the second and Gen X.

By FY 2002 U.S. public higher education expenditures were back up to 1.56% of personal income, but public enrollment was up to 4.0% of the population. Both spending and the share of the population in public higher education institutions have increased since, with the former peaking at 1.75% of personal income in 2010. Rising income, due to the recovery from the Great Recession, pulled down spending to 1.66% of personal income in FY 2012. That was 17.3% higher, relative to income, that it had been 40 years earlier. The increase for New York State over 40 years was 7.7%. Even in FY 2007, before the enrollment gains and personal income decreases of the recession, state and local spending on public higher education was 11.1% above the level of FY 1992 in the U.S. – but just 4.4% above the level of FY 1992 in New York State.

The other states of the Northeast also followed the pattern of decreasing higher education as a percent of personal income as the 1960s generation exited college, with increases later as their children entered. In the end, more is being spent on public higher education, relatively to the income of those paying for it, than in the past.

For auxiliary expenditures data is not available for 1972. State and local government spending in this category was relatively stable as a percent of total personal income from 1977 until the early 2000s, after which it rose rapidly. More was spent even as incomes were relatively stagnant over the past 15 years. From 1992 to 2012, auxiliary spending as a percent of income increased by 25.5% for the U.S., 66.7% in New York State, 85.3% in New Jersey, 81.0% in Connecticut, and 53.9% in Massachusetts. Many other states around the country saw large increases, with Pennsylvania and Texas as exceptions. (Pennsylvania’s auxiliary spending was unusually high in FY 1992 due to a stadium project, as mentioned).

Although New York’ state and local government spending on higher education auxiliary expenditures has increased relatively rapidly over the past 20 years, it remains relatively low, probably because so CUNY has so few students in dormitories and SUNY and CUNY have relatively little sports spending.

The big increase in New York may also be due to the need to replace or rehabilitate buildings constructed in the 1960s, when SUNY and CUNY were being expanded. From 1992 to 2002, the total income of all New York State residents increased 2.32 times (in actual dollars, not adjusted for inflation). Spending on the education part of public higher education expenditures increased 2.68 times, including 2.45 times for operations and 4.51 times for capital expenditures. So the money paid to public higher education professors and administrators did increase somewhat faster than overall personal income in New York, but barely. For auxiliary expenditures, the increase was 3.87 times overall, 3.42 times for operations – and 8.0 times for capital expenditures.

For the U.S. as a whole, faster population growth relative to New York led to a somewhat larger increase in personal income at 2.57 times from 1992 to 2012. Spending on the education part of public higher education expenditures increased 3.07 times, including 3.01 times for operations and 3.58 times for capital expenditures. This shows, once again, that increased higher education spending is a greater explanation for higher tuition outside New York. For auxiliary expenditures, the increase was 3.22 times overall, 3.18 times for operations 3.48 times for capital expenditures.

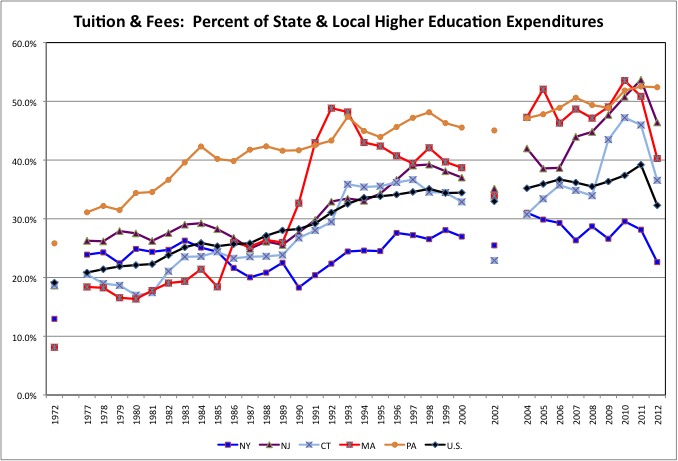

So how much of the total cost of state government higher education is covered by charges — tuition and other fees? According to the 2012 Census of Governments, if you exclude auxiliary expenditures 30.2% of the cost of state higher education expenditures was covered by charges in the U.S. That compares with just 16.6% for New York State, and with 36.6% for New Jersey. Tuition and fees also covered a relatively low percentage of total expenses in California (20.1%) and North Carolina (21.7%), and a relatively high share in Pennsylvania (47.8%) and Oklahoma (38.5%).

This matches up with what is known of comparative tuition levels. SUNY and CUNY have been known as relative bargains, particularly for out of state students, although that is less true than it once was.

Again, however, once can’t help but notice the difference between the attitude of New York politicians between higher education and other public services. For other public services every economic upturn brings demands for public unions and contractors to get more, and every economic downturn sees public service recipients forced to accept less. Taken in total, the tax increases and service cuts are never fully reversed, an occasional (and perhaps temporary) upset like Universal Pre-K aside. Those who control the government, like the one percent, get relatively richer and force everyone else to accept being relative poorer. With regard to public higher education, however, New York’s politicians seem to care a lot more about what people can afford to pay than what the producer interests might want.

Though perhaps not about what the students actually get in exchange. According to anecdotal evidence (the experiences of people I know), it was common back in the 1980s and early 1990 for students at CUNY to take extra years to graduate, because courses required for their majors were simply not offered. And it is common today as well.

Higher education auxiliary expenditures, according to the Census Bureau, are “self-supported (wholly or largely through charges for services) and operated on a commercial basis.” In only eight states, however, including Connecticut and Pennsylvania did these activities break even in FY 2012. In New York, New Jersey and the U.S. as a whole, only about 80.0% of state government higher education auxiliary expenditures were covered by fees. Taxes, tuition or increases in debt are covering about one-fifth, on average, of the cost of “dormitories; cafeterias; bookstores; athletic facilities, contests, or events; student activities; lunch rooms; student health services; college unions; college stores, and the like.”

Taking education and auxiliary expenditures together, tuition and fees covered just over 40.0% of total expenditures on state government higher education in both FY 1992 and FY 2012, nationwide. For New York State the share of expenditures covered by tuition and fees was 25.1% in FY 1992, and 25.5% in FY 2012. Virtually no change. The share of expenditures covered by tuition and fees increased in some states such as New Jersey (from 37.3% to 49.4%) and Pennsylvania (from 42.9% to 59.9%) , but it fell in other such as California (from 33.2% to 27.9%) and Texas (from 34.4% to 31.3%). Based on this data having tuition and fees cover a higher share of state higher education expenditures appears to be a state-by-state issue, rather than an overall trend based on the past 20 years. Contra Demos.

But combining state and local government higher education, to include community colleges, looking further back in time, and looking at actual education and auxiliary expenditures separately, one comes to a completely different conclusion.

Looking just at actual higher education in the U.S. as a whole, tuition and fees covered just 19.1% of state and local government expenditures back in FY 1972, when the 1960s generation was in college. The percent of expenditures covered by tuition and fees increased consistently over the years, and peaked at 39.2% in FY 2011 before dropping to 32.3% in FY 2012. The share covered by tuition and fees had doubled before falling back. Most states around the Northeast including New York and New Jersey, indeed most states in the U.S., followed the national pattern of a rising share of expenditures covered by tuition and fees through FY 2011, followed by a drop.

Why the drop? Perhaps as the student loan burden exploded into the media, those in state legislatures and presidents of public colleges and universities realized they had gone too far. Too late for many students. As state revenues recovered from the Great Recession, perhaps tuition was cut. Note that the Demos analysis stops in FY 2011.

Or perhaps tuition was not reduced, but lots of students were forced to drop out, and tuition and fee income decreased for that reason. Public higher education enrollment fell by 1.7% (230,550) nationwide from 2010 to 2012, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Or perhaps the Baby Boom echo generation will be exiting college (my children are at the end of that generation, as I was at the end of the Baby Boom, and one is already out with another soon to follow) and enrollment – and the tuition and fees that go with it –are set to fall. If that is the case, any fixed costs of public higher education – debts for construction, pensions and health care for retired and soon to retire staff — will be harder to cope with.

If one looks at higher auxiliary expenditures, on the other hand, the percent covered by charges and fees was 106.3% in the U.S. in FY 1977 – they made small profit. Auxiliary expenditures remained profitable in most years until 2000. And then the share of those expenditures covered by fees fell, reaching about 80.0% in FY 2012.

One sees the same pattern in most states. The auxiliary enterprises have become a drain on education. And FY 2012 was a particularly bad year. Pennsylvania also broke even that year, but that state’s low share in FY 1992 was because of high expense that year associated with stadium construction. Is FY 2012 the start of a trend, as a large physical plant is increasingly subsidized as fewer students attend, either because there are fewer students that age or because they are priced out? Will online education leave all those dormitories as stranded assets? Are sports expenditures, now run as an entertainment business, crowding out education?

What the shifting percentages covered by fees implies is that the burden of money losing auxiliary expenditures is being offset by higher tuition for education. That, and rising expenditures overall, are squeezing students in public higher education.

And perhaps one more thing. In addition to taxpayer subsidies and student loans, there is another way to pay for college. Student earnings and parent savings.

As I’ve explained repeatedly in posts on this site, the data says each generation of Americans has been less well paid the one before starting with the back-end of the Baby Boom, and yet the amount most Americans buy didn’t really plunge, and in fact increased, until the Great Recession. One way that consumption was maintained and increased was a decrease in savings, for retirement and other things, including college, despite all kinds of subsidies such as 401Ks and 529. Those mostly benefitted those who would have saved anyway.

And to the extent that prior generations were able to pay for their children’s higher education in part with second mortgages, as my parents did, today’s parents are more likely to have already spent their home equity to get by during spells of unemployment, to replace their SUVs as they wore out, to improve their homes, to maintain their lifestyles after financial setbacks.

The Baby Boomer’s parents were much better off than the Baby Boomer’s grandparents, and benefitted from rising incomes throughout their lives. So their lifestyle expectations were lower than their incomes. Those at the back end of the Baby Boom, and the generations to follow, have lower incomes than their parents, and thus lower incomes relative to their lifestyle expectations.

https://larrylittlefield.wordpress.com/2013/11/10/donald-trump-the-man-of-his-generation/

And that affects their level of savings and debt. Although the one chart I found on median net worth over time shows only a 10.0% drop for those age 45 to 54, about the time parents would be paying for college, from 1984 to 2009

http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2011/11/07/chapter-1-wealth-gaps-by-age/

this presumably does not include the presence or absence of employer-provided retirement benefits, which have been retroactively increased for many public employees and mostly eliminated for everyone else during those years.

Facing retirement with no pension, scant savings, and extensive home mortgages and credit card debts, it would not be surprising if a larger and larger share of U.S. parents have decided they need to contribute less to their children’s higher education. Thus rising student debt is just one aspect of growing financial strain due to, depending on your politics, excessive consumer spending or falling income and rising inequality. And, of course, without excess debt-fueled consumption American businesses would have no one to sell to at prices and levels that supported high profits and executive pay, as I showed here.

A situation that perhaps applies to the higher education business as well.

To high debts and low savings one has to add family dissolution as a potential cause of possible lower parental contributions. The Baby Boomers were the product of generally intact if sometimes imperfect families, with their education a common goal their parents worked toward. With the soaring divorce and remarriage and single parenthood rates of the 1970s and after, however, it is perhaps the case in a higher percent of households the huge burden of college tuition is less a common goal and more a burden to be avoided in pursuit of personal fulfillment.

I am not surprised, based on the political persuasion of those who do academic studies, to be able to quickly Google up analyses of the effect of parent income on student loan debt. And the effect of student loan debt on the student debtor’s subsequent family structure. But not the effect of the parents’ family structure and their children’s student loan debts. Thus we are left with speculation, because only the colleges are in a position to know for sure, and even they might not have the information to compare the time before the divorce and single parenthood boom with after.

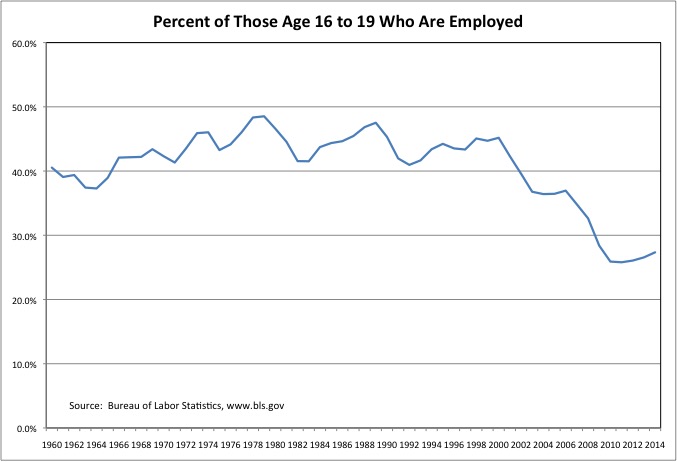

Then there are student earnings. My father was able to pay his way through college almost entirely with work earnings from 1956 to 1960. I was able to pay for about one-third of my own college costs from 1979 to 1983. Most of those my kid’s are have managed to come up with pocket change, in part through jobs at the colleges themselves, which means that higher expenses in part offset those wages.

Why this is may be complicated. It may be that high school students want to work for pay today, due to the greater time pressure of studies and the diminished impetus to work to be able to afford one’s own car (a big deal in the 1960s and 1970s).

Based on personal observation, however, a shortage of jobs may be a greater factor. For a variety of reasons, including the high immigration of the 1990s, welfare reform, and the loss of higher paying jobs for non-college educated adults, there are far more adults pursuing the sort of entry level jobs teens and college students once held. And low-wage businesses generally prefer to hire responsible adults that need to work to avoid hunger and homelessness. Rather than a series of teens who have to have the experience of being fired to achieve a similar level of responsibility.

Then, too, there is the disadvantage of being at the back end of a large generation, whether the Baby Boom or the Baby Boom echo, with a large number of would-be workers already ahead of you in the workforce. For all these reasons and perhaps others, the percent of those age 16 to 19 who are employed plunged after the year 2000, thus reducing students’ ability to save up for their own college.