With Labor Day recently having passed, we got the usual round of stories decrying U.S. inequality, and blaming the decline of unions, the advance of technology, and/or the export of jobs to low wage countries for the fact that the average wage continues to lag behind inflation, as it has for decades. Meanwhile, the U.S. current account balance (the trade deficit plus investment and other flows) continues to be deep in deficit, as it has also been for decades, something President Trump blames on unfair international trade agreements and unfair trade by countries such as China, Mexico, and the European Union. As a result, the Trump Administration is launching trade wars with countries all over the globe. The only import he seems fine with is imported oil, which fuels terrorism and increases greenhouse gas emissions but also allows cheap gasoline.

But if U.S. workers are being paid less and less, to whom are businesses selling in order to make profits? Workers and consumers aren’t two different classes of people; they are the same people at different times of day. And if the U.S. has been importing more than it exports for decades, and has for decades had a financial deficit even when U.S. earnings on investments abroad are taken into account, then how have those imports been paid for? The answer to both those questions is the same. By having Americans, individually and collectively through the government, go deeper and deeper into debt and sell off more and more of our individual futures, and our collective future. Rising debts, public and private, are what allows businesses to pay workers less and yet sell them more, and imports to be paid for without exports. Neither could occur if debts were not rising, and if future retirements were adequately saved for.

It’s a financial house of cards disguising a global crisis of demand, one that would have collapsed in 2008 absent massive government intervention to bail out asset prices and the rich. None of the real problems have been solved since, only deferred at a cost of shifting some of the private debt to the government — just as the Baby Boomers have started to retire in large numbers.

The data and charts used in this post are in this spreadsheet.

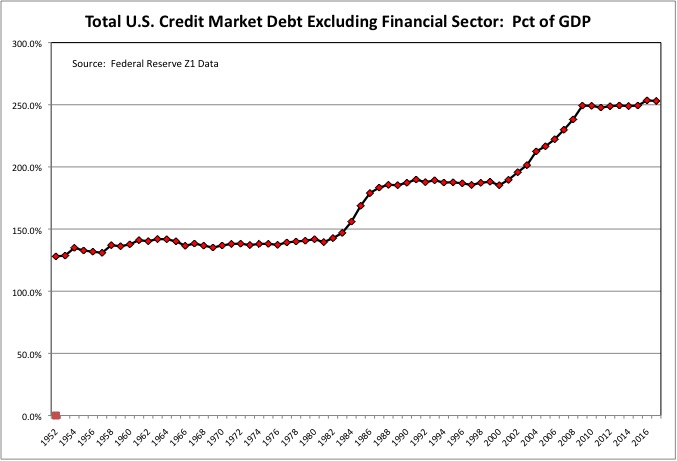

As I have noted in a long series of posts each time annual data on total U.S. credit market debt is released each year, most recently here…

total U.S. credit market debts, public and private, and total debts excluding those financial sector firms owe, were relatively flat as a percent of GDP (the total output of the economy) from 1952 to 1980, but have soared since. Following the financial crisis in 2008 the financial sector has deleveraged, but other debts have edged up in total, with the federal government going deep into debt to prevent the consumer-driven economy from collapsing. Personal debt has decreased, but only because of a huge number of defaults on mortgages, as credit card, student loan, and auto loan debt continue to rise. The trend for non-financial debt is, once again, here.

Along with total U.S. debt, labor’s share of GDP was once thought to be stable over the long term, before the current economic and political era began. But since then the long term trend has been down according to data I retrieved from the data site of the Federal Reserve system.

This becomes even more clear when labor’s share of GDP is charted on a 10-year moving average basis, to limit the effect of the business cycle, on one axis, with total U.S. non-financial debts on the other axis.

As debts have gone up, labor share of GDP has gone down, because rising debts have allowed business sales and GDP to increase – albeit at a slower pace than before 1980 – even though workers have less actual income to spend as a share of the total economy. Otherwise, who would those businesses have sold to? The other way to get higher business sales without higher labor income is to export more as a share of economy. That has contributed to inequality in some parts of the world, but certainly not (as we will see) in the U.S.

One measure of inequality is the Gini Coefficient, which varies from zero if everyone has exactly the same income, to 1 if one person, household or family has all the income, and everyone else has none. I was able to get the U.S. Gini Coefficient for families, as calculated by the U.S. Census Bureau using data from the Current Population Survey, back to 1952.

It was also relatively stable until around 1980, but has soared since. Matching up with the increase in total non-financial debt, as many U.S. families adapted to falling wages by adding more workers (women) to the labor force, by failing to save for retirement, and by going deeper into debt to keep spending going.

The additional workers (working mothers) in some families, and more single parents otherwise, are social trends that also increased inequality among families. But inequality among individual workers has increased as well. I was able to get the Gini Coeffient for individual full time, year round workers going back to 1967, and it shows the same pattern of fluctuating but otherwise being stable before 1980, and then soaring.

But there is a big break – and a big increase in inequality – in the early 1990s. That’s when the pattern of each generation earning less than the only before, which had started with high school dropouts and continued into high school graduates, finally reached college graduates. Since then, it has no longer been possible to buck the tide of falling U.S. income by adding more schooling. Although the conventional wisdom continues to push young people to desperately pursue that degree in a last ditch effort to join what used to be the middle class.

The chart understates the rise in inequality among workers, because one of the ways many have become worse off is that they are no longer full time, year-round. They are contingent, contract workers who often have neither work nor pay – and aren’t paid enough otherwise to make up for it.

Aside from that big break in the early 1990s followed by a temporary flattening out, the long term increase in U.S. worker inequality also more or less matches up with the post-1980 increase in total debts, if the axes are scaled just right.

In general inequality increases when the economy is up, as the better off capture more of the gains, and decreases when the economy is down, as the social safety net mitigates the losses for those at the bottom. The lowest inequality in U.S. history? During the Great Depression. That was also a period of low debt, as the consumer, business and debt explosion of the 1920s was wiped out in a bonfire of bankruptcies. The disappearing debt for some was the disappearing wealth of the wealthy.

That would have happened again in 2008, had not the federal government stepped in at great cost to its own balance sheet to save the banks and the rich. Since 2010 soaring federal debts and the Federal Reserves historically-loose monetary policy has caused asset prices to soar, pumping up the income and wealth of the wealthy. Workers, meanwhile, continue to face decreases in real wages, high unemployment, delayed starts to careers, and ejection from the labor force before the planned date of retirement. And for those born after 1957 or so a rising death rate and falling life expectancy. So inequality has likely risen again. According to The Economist…

The state had no choice but to stand behind failing banks, but it took the ill-judged decision to all but abandon insolvent households. Perhaps 9m Americans lost their homes in the recession; unemployment rose by over 8m. While households paid down debt, consumer spending was ravaged.

According to Bloomberg News…

Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner and President Obama

Saw the crisis primarily as a macroeconomic event that could be solved through a series of aggressive technical fixes. As they arranged the mergers, bailouts, and Fed lifelines that rescued corporations from Citigroup to General Motors to Goldman Sachs, they prided themselves on their ability to tune out the public’s justified anger at the greed and recklessness exhibited by financiers and mortgage lenders.

As a macroeconomic event, rather than as the collapse of an entire, unsustainable, debt fueled economic era that began in 1980.

Financial crises are every bit as much about politics as economics. How could they not be? Millions of people lost their job, their home, their retirement account—or all three—and fell out of the middle class. Many more live with a gnawing anxiety that they still could. Wages were stagnant when the crisis hit and have remained so throughout the recovery. Recently the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that U.S. workers’ share of nonfarm income has fallen close to a post-World War II low.

But personal material conditions alone didn’t drive the public response to the crisis. There was a moral component as well. A bitter irony dawning on Geithner at the time of our meeting was that a substantial number of Americans saw the rising stock market not as a gauge of economic revitalization but as an infuriating reminder that the financial overclass responsible for the crisis not only got off scot-free but was also getting richer in the bargain. The iniquity stung.

So desperate Americans voted for Donald Trump for President. And Donald Trump has proceeded to advance an agenda of de-regulation of the financial sector and tax cuts for the rich and corporations.

As one study after another shows, average U.S. wages have not increased for decades, even in the face of higher educational attainment. And the average disguises the extent to which those in later-born generations are paid far less than those born earlier who have similar educational backgrounds and jobs, with income and wealth peaking for those born from 1930 to 1957 or so. Those who entered the labor force before the average male wage peaked in 1973, or at least before debt and inequality started to soar in after 1980. While wages have risen recently…

After adjusting for inflation… today’s average hourly wage has just about the same purchasing power it did in 1978, following a long slide in the 1980s and early 1990s and bumpy, inconsistent growth since then. In fact, in real terms average hourly earnings peaked more than 45 years ago: The $4.03-an-hour rate recorded in January 1973 had the same purchasing power that $23.68 would today.

Cash money isn’t the only way workers are compensated, of course – health insurance, retirement-account contributions, tuition reimbursement, transit subsidies and other benefits all can be part of the package. But wages and salaries are the biggest (about 70%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics) and most visible component of employee compensation.

Wage stagnation has been a subject of much economic analysis and commentary, though perhaps predictably there’s little agreement about what’s causing it (or, indeed, whether the BLS data adequately capture what’s going on). One theory is that rising benefit costs – particularly employer-provided health insurance – may be constraining employers’ ability or willingness to raise cash wages.

As I showed in this post using data from the Local Area Personal Income data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, however…

while the cost of benefits did soar as a percentage of wages from 1969 through the early 1990s – when the big break in worker income inequality took place – it has been relatively flat since, cyclical changes aside.

Nationwide, the cost of employer contributions to employee pensions, health insurance and other benefits did soar from 8.4% of private sector wages and salaries in 1969 to 16.2% in 1992. Since then, however, benefits have been stagnant as a percent of wages and salaries, aside from cyclical changes. Benefits increase as a percent of total wages in recessions, when wages fall, and decrease in expansions, when wages rise. But employer benefit costs were 16.1% of total wages in 2016, about the same as 25 years earlier.

Moreover, the Bureau of Economic Analysis doesn’t make wages and benefit data readily available for public sector and private sector workers separately. The data in the chart above includes state and local government workers, and we know that their benefit costs – notably taxpayer pension contributions and retiree health care funding – have soared relative to the wages and salaries of government workers still on the job.

Therefore, employer benefit costs must have actually fallen in the private sector, to keep the total flat. And that is what ought to be expected, given that fewer and fewer private sector workers get employer-funded health insurance or pensions, employee health insurance copayments have soared, and employer contributions to 401k “defined contribution plans” have been cut with each recession. These are actually “undefined contribution plans.”

The trend is similar for mandated employer contributions to government social insurance plans, such as Social Security, Medicare, unemployment insurance, etc. These increased from 4.4% of wages and salaries in 1969 to 7.5% in 1984, due to an increase in the payroll tax to “save Social Security,” but there has been little change since, with mandated employer social insurance contributions equaling just 7.2% of wages and salaries in 2016. Obamacare didn’t more the needle.

So if workers have less, to whom are businesses selling? Where are people getting the money to buy things? You don’t hear in the media, or in the statements of economists, that has debt created inequality, and that one is not possible without the other. So what are the common explanations of rising inequality that one does hear today?

The first explanation for rising inequality is technology and automation. With information technology and robots, and next coming for the jobs of the college-educated “artificial intelligence,” it is possible to produce goods and services with fewer and fewer workers. Therefore, it is argued, those who control the investments in information technology and robots can earn massive amounts, even as the shrinking number of workers has their pay competed down by the rising number of unemployed.

But this ignores the other side of the economy, the sales side. Who are these masters of technology going to sell to? The robots? Either workers have to be paid enough to buy what the robots produce, or they have be given the money to buy what the robots produce. Unless they borrow to buy what the robots produce, or the government borrows for them, until they can’t anymore and the whole financial house of cards collapses.

The sector with the most technology and automation? Agriculture. Farming required half of all U.S. workers to produce the food we needed a century ago, compared with just a percent or two today. Does that mean that every farmer is a $billionaire, and everyone else still spending half their income on food? No. The gains to farmers of no longer having to pay as many farm workers were lost in the food marketplace, as food prices fell relative to the overall economy. Because farmers had to have someone to sell to. Today many farmers do well, but only because the government intervened to keep their prices from going even lower, and subsidized them.

A second explanation for rising inequality is political: having captured the U.S. federal government, many assert, the rich have managed to beat down the unions which allowed labor to bargain with capital, and ordinary workers to bargain with those at the top. Once the Reagan Administration made union-busting respectable, everyone but the executives at the top became worse off.

In most rich countries, real pay has grown by at most 1% per year, on average, since 2000. For low-wage workers the stagnation has been more severe and prolonged: between 1979 and 2016, pay adjusted for inflation for the bottom fifth of American earners barely rose at all. Politicians are scrambling for scapegoats and solutions. But addressing stagnant wages requires a better understanding of the relationship between pay, productivity and power.

There is good reason to think that power imbalances play a big part in the rich world’s wage stagnation. Product markets have become more concentrated, meaning that fewer firms account for a larger share of output. That increases companies’ power in labour markets, since workers are less able to find alternative employment or to pit rival employers against each other in a bidding war. In a recent paper Suresh Naidu, Eric Posner and Glen Weyl estimate that this rise in firms’ power may reduce labour’s share of national income by as much as a fifth. They argue that one way to help struggling workers might be to use antitrust policies to make product markets less concentrated and more competitive.

A complementary approach would be to increase workers’ power. Historically, this has been most effectively done by bringing more workers into unions.

Since apparently, employers have their own unions to bargain wages down in “right to work” states.

There are two problems with this perspective. First, after some successes on the social justice front in the first half of the 20th century, I’m not sure unions made workers in general better off at the expense of investors and executives. They just made some politically powerful workers better off at the expense of others. The heyday of American unionism was also the heyday or white male wages, but women and racial minorities were confined to lower-paid economic ghettos at the time.

More recently the public employee unions have used their clout to have their pensions retroactively increased, even as active and required public employees “voted” for lower wages and benefits for other workers by seeking the best deal possible every time they went shopping. It is only because government is something you are forced to pay for, whether you think it is a good deal or not, that members of public employee unions have been able to force other workers to accept less and pay more. They are out of solidarity with the rest of the American workforce.

Moreover, even if the ascendance of the Koch Brothers and the absence of unions leads to a minimum wage of $2.50 per hour, and enough desperate competition for jobs to avoid starvation that most Americans earn no more than that, business would run head-long into the very same problem. Who are they going to sell to? The Chinese, Mexicans and Arabs? They have more inequality than we do.

The third explanation for rising inequality is globalization and trade. With the rise of free trade, according to this theory, businesses have been able to keep selling to U.S. worker while in effect replacing them with lower paid workers from poor countries, keeping the difference as higher profit. The result has been a shift in economic power from the U.S. to China.

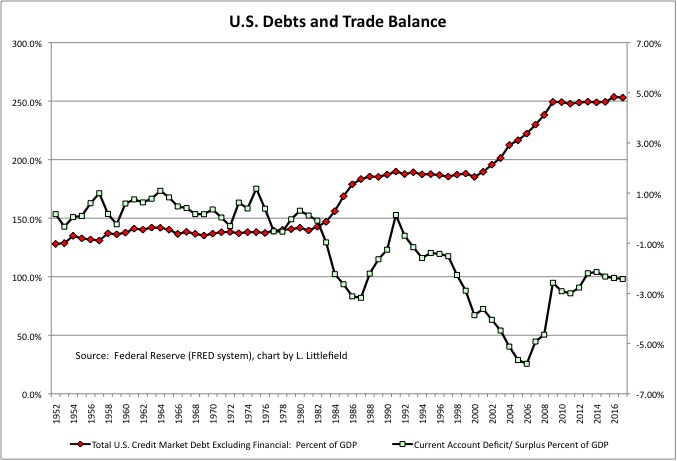

But where did the U.S. get the money needed to buy all that stuff from China, Mexico and Germany (and oil from the Middle East), and to run a current account deficit for all these years? We, collectively, borrowed it.

Data from the Federal Reserve showed that the U.S. current account was basically in balance – but with the U.S. usually somewhat in surplus – from 1952 to around 1980. At the time, studying development economics, I learned that to some critics U.S. foreign aid was nothing but a subsidy to U.S. corporations, since it provided poor countries with the money they needed to buy U.S. goods. The other alternative, the one that allowed developing counties, notably in Latin America, to import more than they exported was soaring public and private debts. In a reverse of the post-1980 pattern, our current account surplus caused some other countries’ current account deficit. The result was a long series of foreign debt and currency crises, followed by severe austerity and economic calamity for ordinary people.

https://economics.rabobank.com/publications/2013/september/the-mexican-1982-debt-crisis/

Since the early 1980s, the U.S. economic situation has been absolutely Argentine, with Americans importing more than they export year after year – other than 1991 when the rest of the Arab oil exporters paid the U.S. to drive Saddam Hussein out if Kuwait during the Gulf War. Americans, collectively, have been consuming more than they produce by importing more than they export and earn, net, on investments abroad. All to finance higher consumption, higher than we could pay for with income by two percent to six percent per year.

This was a huge party for the richest generations in U.S. history, with some getting to party a hell of a lot more than most. Paid for by the sale of their children’s collective futures and in some cases their own individual future.

Had the U.S. not borrowed, it would only have been able to buy as much from other countries as we sold to other countries, and the effect of trade on employment and equality would have been negligible. We don’t have a trade problem. We have a trade deficit problem that is really a debt problem. And it isn’t getting any better.

Because the Trump Administration is ramping up total U.S. debts again, the trade deficit (and inequality) are once again rising.

Longer term, in what part of the economy has trade wiped out the most jobs? How about clothing, which is almost 100 percent imported today. So does that mean everyone who works in the clothing industry earns $millions every year while ordinary people still spend as much for clothes as they did 50 years ago? No. I remember when my middle class mother had to patch our blue jeans, and it was still cheaper to make clothes than to buy them. Now new clothing is so cheap that no one wants hand-me-downs anymore, unless they are college-educated “hipsters.” In the clothing industry lower wages have just meant lower prices, benefitting all workers and not investors and executives.

Americans, however, don’t want to hear that their own credit card debt has caused the trade gap. American businesses don’t want to hear that their high level of profit and executive pay has been made possible only by a sell off of the future. They want to blame someone else.

Have the Chinese engaged in economic espionage, theft of technology and intellectual property, and other unfair trade practices? Maybe. But they aren’t the first developing country to do so at the expense of the world’s dominant economic and political power of the time.

http://foreignpolicy.com/2012/12/06/we-were-pirates-too/

Today, Chinese espionage is widely assumed to have targeted virtually all big American technology companies. A long list of firms, including Apple, Boeing, Dow Chemical, Dupont, Ford, Motorola, Northrup Grumman, and General Motors, have pursued successful criminal actionsagainst Chinese moles and other agents.

If anything, the early Americans were even more brazen about their ambitions. Entrepreneurs advertised openly for skilled British operatives who were willing to risk arrest and imprisonment for sneaking machine designsout of the country. Tench Coxe, Alexander Hamilton’s deputy at Treasury, created a system of bounties to entice sellers of trade secrets, and sent an agent to steal machine drawings, but he was arrested. While skilled operatives were happy to take U.S. bounties, few of them actually knew how to build the machines or how to run a cotton plant.

The breakthrough came in the person of Samuel Slater. As a young farm boy, he served as an indentured apprentice to Jedidiah Strutt, one of the early developers of industrial-scale powered cotton spinning. As Strutt came to appreciate Slater’s great talents, he employed him as an assistant in constructing and starting up new plants. (In his signed indenture, Slater promised to “faithfully … serve [Strutt’s] Secrets.”)

Worried about his future in England, Slater made the jump to the United States when he was 21, bringing an unusually deep background in mechanized spinning.

Emigrating under an assumed name, he answered an ad from Moses Brown, a leading Providence merchant, who had been badly stung by ersatz British spinning machinery. Brown was sufficiently impressed by Slater to finance a factory partnership, and over the next 15 years, Slater, Brown, their partners, and the many people they trained created a powered thread-making empire that stretched throughout New England and down into the Middle Atlantic states. Former president Andrew Jackson called Slater “The Father of the American Industrial Revolution,” the Brits called him “Slater the Traitor.”

While Donald Trump chooses to blame other nations and immigrants for the nation’s economic problems, traditional economists just keep repeating the mantra that “the theory of comparative advantage proves that free trade makes almost everyone better off!” As a statement of fact that does not need to be defended. Although sometimes they add lots of equations to prove it further.

https://economics.mit.edu/files/4350

What they fail to consider is that the theory of comparative advantage assumes that rising imports, which cost jobs, are paid for by rising exports that create jobs.

What if that isn’t true? What if a large share of the imports are paid for by debt, until the excess import country is so deep in debt it can’t pay the interest anymore, and its economy collapses? Has anyone considered this? Or have they just assumed that a negative current account balance just can’tgo on for four decades, because the currency of the country with a huge current account deficit and external debt would fall, and this make imports more expensive.

Except that with regard to the dollar, this hasn’t happened, and the current account has never gotten back into balance. And yet it seems as if no economists have noticed. Perhaps because they got an “A” in graduate school by showing that “the theory of comparative advantage proves that free trade makes almost everyone better off!” and haven’t opened their eyes and mind since age 25.

The financial crisis that took place a decade ago was merely a symptom of an underlying disease that has gotten worse since. A financial heart attack was treated, but the economic cancer was allowed to rage on. With rising federal debts substituting for rising personal debts – putting Social Security and Medicare at risk and slashing infrastructure investment. All kinds of interventions have taken place to keep people who are being paid less still spending, to the point of handing out mortgages with 50 percent of younger generations’ incomes going to debt so they can overpay for older generations’ houses.

Might most people now under the age of 60 have been better off if the whole thing had been allowed to collapse in 2008? That might be worth thinking about, because none of the real problems have been solved, and with asset prices re-inflated far past any income available to support them, another economic heart attack is inevitable. And when it happens, most of us who are not Silicon Valley $billionaries will not be able to flee to a bunker in New Zealand.

https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2018-rich-new-zealand-doomsday-preppers/?srnd=premium

Some academics have indeed pointed to monopsony as a factor in driving down wages. Especially in rural areas that never had that many employment options to begin with. And of course the idea that fast food outfits need non-competes or anti-poaching to preserve their “investment” in employee training is laughable on its face. Don’t forget hi-tech had its own anti-poaching conspiracies revealed thru several class action lawsuits. Some have pointed to economic concentration (not just companies but geographic job opportunities) as hindering employment and wages as most workers moving to such job centers are worse off due to exorbitant cost of living. Small wonder job relocations and employee mobility fell to 30 year lows. Reminds me of the supposed “puzzle” over restrained wage growth despite supposedly low unemployment. But as this Moody’s Analytics article points out, by using prime age non-employment rate instead of a flawed unemployment rate, there is plenty of labor slack still: https://www.economy.com/dismal/analysis/datapoints/296127/There-Is-No-US-Wage-Growth-Mystery. But any ordinary working stiff already knows this intuitively. Did I mention that some economists think the entire field in in crisis because theory and reality keep diverging? And as you alluded to, the alleged full employment of the mid 20th century conveniently ignores the widespread economic disenfranchisement of women and minorities.

I have no doubt China is taking advantage of America the same way we did against Britain. What I don’t get is why Western companies seem eager to turn over proprietary knowledge for market access to eventual competitors. Short-termism at its finest. And the theory of competitive advantage assumed countries having comparable labor costs, not 10x or higher ratios. So again, theory not quite aligning with reality, blithely asserting that “everyone” is better off.

Like you, I sometimes wonder if letting the system flush out its debt via bankruptcy would have been a better outcome. Especially as the bailout didn’t include ordinary folks. Not just to effect financial repair, but reset dysfunctional political and corporate institutions too.

It’s easy for me to say. After all, after 1929 and the Great Depression the Russians got Stalin, the Germans got Hitler, the Japanese got Tojo, and we got FDR.

Then again, have you heard anything about what is going on in Washington these days?

The interesting comparison is Ireland and Iceland. Ireland bailed them out, Iceland nationalized them and, where there was malfeasance, jailed them. So where are they now a decade later? That comparison would interest me.

Here is a quote from Basic Rights by Shue, something I read in college.

“Nietzsche, who holds strong title to being the most misunderstood and most underrated philosopher of the last century, considered much of conventional morality – and not conceptions of rights only – to be an attempt by the powerless to restrain the powerful: an enormous net of fine mesh busily woven around the strong by the masses of the weak. And he was disgusted by it, as if fleas were pestering a magnificent leopard or ordinary ivy were weighing down a soaring oak. In recoiling from Nietzsche’s assessment of morality, many have dismissed too quickly his insightful analysis of morality…One of the chief purposes of morality in general, and certainly conceptions of rights, and of basic rights above all, is indeed to provide at least minimal protection against utter helplessness to those too weak to protect themselves.”

So which philosopher pointed out that rising inequality creates a shortfall in final demand, leading to a series of crises due to rising debts, because the desire of each individual firm to minimize its labor costs is in “contradiction” with the desire of all firms to increase their sales? Karl Marx. That is his central critique of capitalism.

Marx’s solutions to the problem, or those of his followers, didn’t work out that well. Mostly because they ignored the need for what I call “voluntaryness” in human relations as a check on human selfishness.

When a relationship becomes involuntary in one direction – as when has no choice but to pay for a good or service and no options – those producing that good or service will inevitably decide, bit by bit, that fairness require that others pay more, accept less, or some combination of both. As one finds, for example, in parts of the public sector in New York City. Or increasingly, due to a lack of anti-trust enforcement, in the private sector in the United States. Marx simply believed without evidence that, free from the social conditioning of the capitalist system, people would be better people, and serve each other voluntarily. As did the early Christians. It didn’t work out that way for either.

However, in recoiling from Marx’s solutions to the problems of capitalism, many have dismissed too quickly his insightful analysis of problems of capitalism. You can’t analyze one half of the economy – the production/labor market side – independently of the other – the sales/consumer spending side. Henry Ford, who wanted to pay enough so his workers could afford his cars, would have agreed.